Narratives have power, both good and bad. On one hand, stories can create change. On the other hand, they can serve to obscure opposing viewpoints.

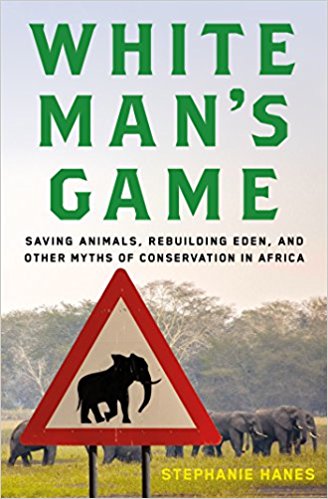

Journalist Stephanie Hanes explores this potentially dangerous dichotomy in her new book “White Man’s Game: Saving Animals, Rebuilding Eden, and Other Myths of Conservation in Africa” (Metropolitan Books, $28), where she takes particular aim at conservationists, whom she accuses of often ignoring — willfully or otherwise — the narratives of the people around them. This, she claims, causes many Western-led conservation projects in Africa to have unintended consequences or even flop completely: for example, fences that protect people but disrupt animal migration corridors. “The reason so many Western projects in Africa fail,” she writes, “is not because of bad planning or poor investment strategies…[but] because we are stuck in our own mental framework. We cannot see the other narratives, even when they actively clash with our own.”

Hanes takes her book’s own narrative all the way back to 18th century explorer James Bruce, a Scottish noble whose bestselling five-volume series recounting travels up the Nile River set the stage for the “adventurer-type approach to the continent” later embodied by former president Teddy Roosevelt, whose own blood-soaked expedition to Africa resulted in his famous “collection” of more than 23,000 museum specimens. Both men were perceived by Western audiences as gallant heroes exploring savage lands, but their actions also created a somewhat ironic narrative of Africa “under threat,” which still echoes through conservation efforts in the modern era. As Hanes writes at one point, the “conservationist story of local people destroying their own land and needing outsider help to change their ways” belies the fact that local people served as stewards of their own land for generations before Westerners arrived.

Hanes takes her book’s own narrative all the way back to 18th century explorer James Bruce, a Scottish noble whose bestselling five-volume series recounting travels up the Nile River set the stage for the “adventurer-type approach to the continent” later embodied by former president Teddy Roosevelt, whose own blood-soaked expedition to Africa resulted in his famous “collection” of more than 23,000 museum specimens. Both men were perceived by Western audiences as gallant heroes exploring savage lands, but their actions also created a somewhat ironic narrative of Africa “under threat,” which still echoes through conservation efforts in the modern era. As Hanes writes at one point, the “conservationist story of local people destroying their own land and needing outsider help to change their ways” belies the fact that local people served as stewards of their own land for generations before Westerners arrived.

Damning history out of the way, Hanes hits upon a number of modern initiatives but concentrates the bulk of her book on one recent effort: the Carr Foundation’s multimillion-dollar project to restore the wildlife, ecology and people of Mozambique’s once-bountiful Gorongosa National Park.

Since the project’s genesis in 2004, Gorongosa has been the subject of magazine articles, books and documentaries. Virtually all of these write-ups heap praise upon the Carr Foundation’s near-herculean efforts. Hanes takes a different view. She argues that the Gorongosa project is actually a bit of a failure, both for the wildlife — which sometimes didn’t survive for long after being transplanted back into the park — and for the people living in and around the region, whose health and well-being have not necessarily improved as promised or predicted.

Hanes points out numerous small, cultural mistakes, such as asking people to replant a deforested area where planting trees was actually perceived as a way to claim or steal land, or handling a lizard species whose appearance was seen as a bad omen. These errors invariably set efforts back, she writes, while conservationists responded by saying things like “they need to understand. We’re here to help.”

Other examples show more direct consequences. For example, Hanes writes of a former poacher who was hired in the early stages of Gorongosa’s construction project. He stopped poaching for a year while he earned a salary, but then the project finished and the money dried up. With no new jobs being offered, and no reason to remain loyal to the project, he immediately went back to poaching. Hanes recounts how other poachers — who all too often killed the animals that had been imported into the park at great expense — were frequently beaten by official personnel or essentially forced into near-slave labor to pay the park back for their crimes.

Her harshest criticism, however, stems from what she sees as the inability of some philanthropists and conservationists to recognize and understand the spiritual beliefs and narratives of the people they are serving, such as the communities who depend on Gorongosa for their own survival. Those beliefs, she writes, are the history that still lives on as part of modern-day life as spirits — either ancestors who serve as an unbroken chain of leadership, or as angry, vengeful gamba created by Portuguese occupation or Mozambique’s bloody civil war. The narratives of those days-gone-by remain a part of daily life, even if Westerners did not perceive them. Hanes says this inability to view the reality of the people around them either delayed or doomed at least some portions of the Gorongosa project.

The book makes valuable points that aren’t just about conservation — we could all do better to consider narratives outside our own heads. As for Gorongosa, where restoration efforts continue despite Mozambique’s continuing financial and political conflict, the narrative of the park is still being written.

Revelator Reads: 7 New Environmental Books for July

My first question when I see anything like this is: Is this based on actual environmental concerns, primarily concerns for wildlife and the most effective strategies for preservation and restoration, or is this just more anthropocentric drivel prioritizing people over everything else. While I totally oppose colonialism, I even more strongly oppose destruction of the natural environment, including killing wildlife for any reason other than to eat it. This article and the book it’s about seem to be the anthropocentric kind, unfortunately.