Patterns emerge in life, and in death.

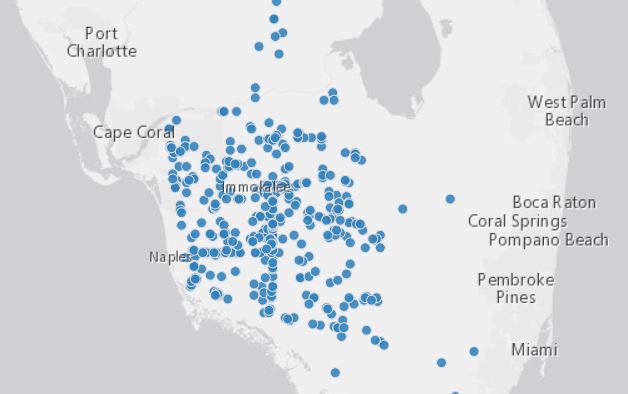

Those patterns aren’t always immediately clear. When you first look at this map on the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s website, all you see is a collection of blue dots, hundreds of them — an amorphous cloud over the southwestern portion of the state.

Zoom in closer and the patterns begin to reveal themselves. The blue dots take on clearer shapes. Toward the Gulf Coast, a dozen dots form a straight line between Fort Myers and Bonita Springs. Another pattern of about 20 dots begins near the city of Naples and stretches out to the east. At one point on that line, roughly 30 miles inland, another straight line emerges, this one heading north and south. This third line is littered with dozens of blue dots.

Only they’re not just dots. Each of these pale blue spots marks the location where a Florida panther has been found dead over the past 46 years.

And those lines? They’re roads. Routes 41, 29 and 75, best known as the Everglades Parkway.

Roads kill, especially if you’re a critically endangered Florida panther.

Last year, according to newly released data, at least 24 Florida panthers died after being struck by vehicles on these and other Florida roads — 83 percent of the 30 known panther fatalities in the state in 2017. (Four additional deaths were caused by panthers killing other cats that invaded their territories; two deaths were from unknown causes.)

No one knows exactly how many of the big cats still roam the state, but the most recent estimates put the population at somewhere between 120 and 230 adults and juveniles, a number that’s almost certainly on the decline. According to those estimates, this year’s dead could represent somewhere between 13 and 25 percent of the species’ entire viable population. Even worse, more than a third of this year’s mortalities were breeding-age females, limiting the cats’ chance of bouncing back.

Of course, 2017 didn’t see the highest ever number of annual panther fatalities in the state, but it would be hard to beat the 42 found dead each year in 2015 and 2016, the two worst years on record since the big cats were protected under 1967’s predecessor law to the Endangered Species Act. The total number of vehicular fatalities was also down from the previous two years, but it did represent a new record for the percentage of panthers killed by vehicles.

Fortunately, even amidst the deaths there’s some sign of life. At least 19 panthers are known to have been born during the course of 2017 — a slight improvement over the 14 cubs observed in 2016 and the 15 cubs in 2015 — but that’s not enough to compensate for the cost of the dead on the population as a whole.

And yes, the pattern of deaths and low birth rates over the past three years has undoubtedly reduced the number of surviving Florida panthers. More of the animals die each year than are being born. “The Florida panther is suffering slow-motion extinction,” said Jeff Ruch, executive director of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, in a recent public statement.

What comes next? In all likelihood the news about Florida panthers will continue to be dire. “There are currently no coherent efforts to save the Florida panther from extirpation in the wild, and during a Trump presidency we are unlikely to see one emerge,” Ruch said. In fact the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is currently considering whether or not panthers should retain their full protected status under the Endangered Species Act, or even if they should still be considered their own subspecies, a matter of ongoing taxonomic debate.

After more than a decade of writing about these big cats, I expect that without drastic steps the number of Florida panthers killed each year will continue to hit new records as the population declines on a curve toward oblivion. That pattern is clear, and we need to change it.

There are systems of alerts being used in Australia that rely on ear or collar tags on the protected animals, which when they get a certain distance from the detectors by the road will set off flashing signs, to warn cars a vulnerable animal is near the road. Also, what is the status of disease spread from domestic cats (Felis catus) to the panthers? I remember a few years ago there was a disease outbreak that killed 3 or more panthers in one year.

The collar warnings are a good system, but only a few panthers are currently collared and the budget for that program has been flatlined, so monitoring is poised to cease. A few of the deaths were from unknown causes, which could conceivably be due to disease, but I don’t think we’ve seen much of that in the most recent couple of years.

What about individual donations or gofundme campaigns, for public citizens to “adopt” a panther to be collared? Likewise, corridors must be built, which would also create jobs, and help mitigate human invasion and habitat destruction/fragmentation. We must direct our compassion and protection for these beings who are essential for healthy ecosystems creatively and quickly.

Johanna and Ruddy are fully correct. However, it all comes down to the good will of the people, authorities and the budgets given to save a precious animal………. something tells me, well, think you all get it, right?

The photo credit should read National Park Service (not “Parks”). But thanks for an otherwise informative article.

Corrected — and thanks!

Roads are the pathway to the FL panther’s extinction. According to the stats you present here, we have 8 YEARS MAX before the panther is forced into extinction by way of the vehicle (not including new birth rates). Either way, they are dying at an average of up to 2 times the birthrate. That isn’t sustainable in any play book. Another reason panthers are dying is due to habitat loss and fragmentation which forces them into each other’s territories and to attack each other. The “drastic” measure needed won’t be taken in FL unless people on the ground and local governments take measures, then maybe the state will follow suite as it has dragged its feet thus far.

There needs to be:

1) real designated critical habitat for the FL panther by FWS

2) A halt on any new developments in panther habitat. (Including FPL’s proposed natural gas plant)

3) Restoration and connection of fragmented habitat and corridors

4) A road closure of 41, 29 and 75 for 5-10 years open only to local traffic. It would have to be lead by the locals, tribal members and tribal councils that need the roads in order for it to have any teeth and be successful.

5) reduction in speed limits on these roads

Really the roads need to be torn up. But there are so many people dependent on these roads, if the people that need these roads took active local action, something could be done, otherwise…

who will be the driver that slaughters the last FL panther?

The quickest solution is elevated roadways over habitat we want to maintain. Once they’re built, the habitat no longer has roadways on the ground of panther habitat. Nature selects for those who avoid moving forms of transportation, especially if those forms are piloted by the ecologically illiterate, still the default setting in western culture generally but in the US specifically. Raised roadways render fairly harmless the ecologically illiterate, even the willfully ecologically illiterate.

A difficult though perhaps permanent solution is to amend ecological literacy into western culture, now stupidly hanging onto its pre-ecological basis: aka ecological illiteracy. The psychodrama of a public burning of western culture, a D- culture, might hasten the amendment. Western culture enslaves the many to support the few in the opulence to which they, as nobles and/or priests, became accustomed. Slavery thrives, thanks to western culture. What is a policy that conserves poverty and soul murder?

Elevated roadways is only a band-aid, but, to save the panther, it’s the most likely to take place in time to prevent panther extinction due to human supremacy, which trumps white supremacy for its degree of stupidity – perhaps.

The expense of elevated roadways would be so high I don’t think you would get anyone doing this – and the disruption to the environment while they constructed them would be horrendous. . However underpasses which the animals would soon learn to use would be much cheaper.

That has been tried and the underpasses become ambush sites for predators (like the Florida panther) to pick off prey so easy that other species (prey animals) soon face extinction.

The solution to the ecological dilemma we’ve let Massa force us into is to drown western culture in the bathtub and start over with something that makes a little bit of sense. I vote for ecological literacy.